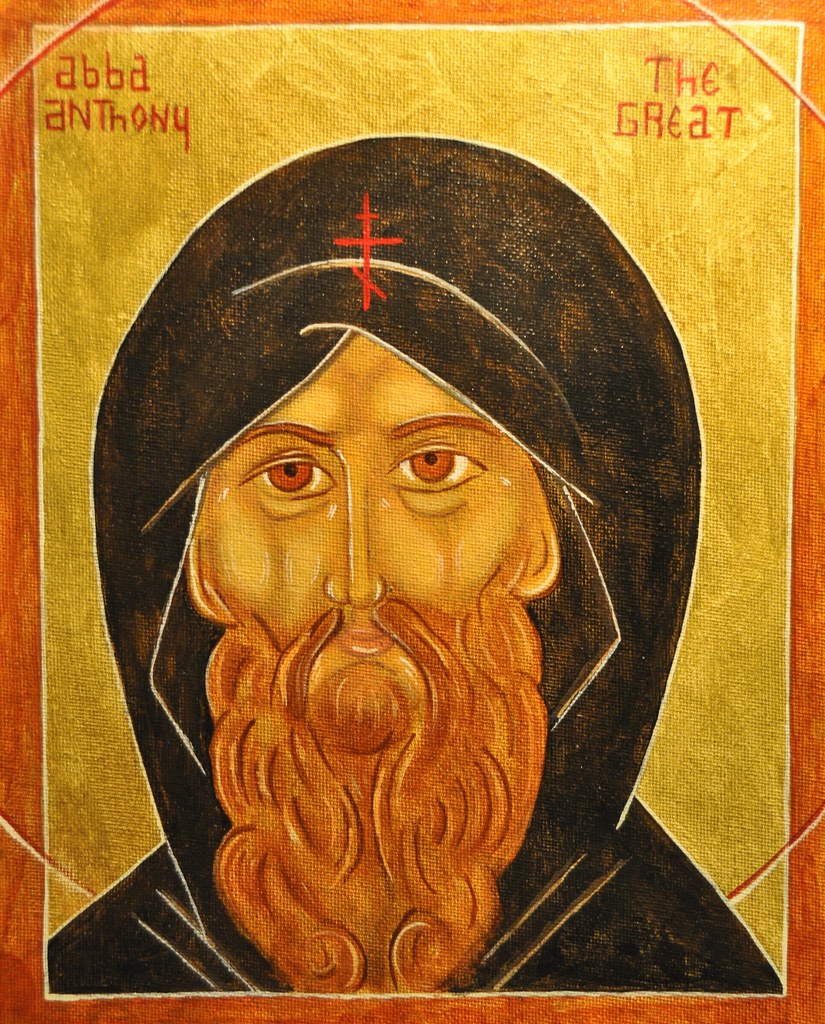

Historically, Christians held two main traditions regarding conflict: pacifism and just war theory. Originally, Christians refused to fight for the empire. They stood down if they converted to Christianity while soldiers. Saint Martin of Tours was the poster child for all who chose to follow Christ and no earthly commander. Mennonites, Quakers, and Brethren persist in this stance, while insisting that pacifism is not passivity. Rejecting the logic of war, Christian pacifism actively pursues non-violent solutions to social and international conflicts. Even the ark of fraternity recognizes that abstainers are sitting ducks without strong creative engagement.

Under Constantine, Christianity became a state religion, creating confusion. Not following a pagan king into battle made sense; how about a Christian monarch? A church-state partnership meant rulers now expected a blessing on their wars. Saint Augustine posited that Christians might fight in a just war. He left the defining of terms to Thomas Aquinas.

Aquinas sought to restrict war. First, violence can be waged only by the proper authority. Also, the purpose must be just: national interest is insufficient. Thirdly, peace must be the goal of every soldier. Students of Aquinas added that violence must be the last resort. War was permissible in self-defense. The means must be proportionate. A just fight loses legitimacy if civilians or hostages are harmed.

The position of “just peace” was ventured by Pope John XXIII (Pacem in Terris, 1963). Peace is more than the absence of war, he argued; it’s grounded in the justice that sustains peace. Recent popes have questioned if proportionality is possible in a world with doomsday weapons. Pope Paul VI, in his 1965 speech at the U.N., declared: “Never again war, never again war! It is peace, peace, that has to guide the destiny of the nations!” Pope John Paul II hoped the world would learn to “fight for justice without violence.”

On the 50th World Day of Peace, Pope Francis described humanity as “engaged in a horrifying world war fought piecemeal”—through war, terrorism, crime, violence against women and children, abuse of migrants, human trafficking, and environmental devastation. The pope recommended: abolishing nuclear weapons, an ethic of fraternity, the will to resolve conflict diplomatically, and a commitment to active peace-building at every level.

Scripture: Isaiah 2:2-5; Micah 4:1-4; Proverbs 8:15-16; Psalm 118:8-9; 146:3-4; Matthew 5:9; 38-48; Romans 13:1-4; Ephesians 4:23; 6:10-17; 1 Peter 2:13-17

Books: I’d Rather Teach Peace, by Colman McCarthy (Orbis Books, 2008); Jesus Christ, Peacemaker: A New Theology of Peace, by Terrence J. Rynne (Orbis Books, 2014)