Begin with the Christian premise that obliges us toward peace and against war. Just war theory is the body of moral reasoning developed to discern when the primary bias against war may shift toward an obligation to protect and defend. History proves there are times when violence can't be avoided and must be engaged. Just war theory insists that war can never serve a political or economic purpose. Military action must serve a fundamentally moral purpose. Both societies and individuals are accountable for the decision to fight and must soberly consider why they do.

The first principle of just war tradition, then, defines war as a moral issue. The second holds that even a just war can't be engaged without limits or restraints. Theologian Paul Wadell notes that even a legitimate war is an occasion to be mourned, not celebrated. The duty not to harm or injure another is "intrinsically binding" for Christians. Acts of violence even during wartime are to be avoided when possible and limited when necessary, to protect the innocent and to restore justice.

In the early church, pacifism preceded just war tradition. Until Constantine's reign in the fourth century, soldiers who became Christians laid down their arms. Pacifism was necessary for two reasons: because military service involved idolatry toward the emperor, and because killing was a direct violation of the command of Jesus to love your enemy. The alliance of church with state under Constantine ensured that church policy leaned toward supporting the interests of the empire. Christianity's original pacifism wavered. Fourth-century theologians Ambrose and Augustine developed arguments that could, under limited conditions, make war not only permissible but obligatory in the service of a victimized neighbor. Augustine particularly emphasized that a sinful world often presents no perfect solutions to unjust situations.

Just war theory offers eight criteria for engagement. Seven determine whether a conflict is justified, including: just cause, competent authority, last resort, comparative justice, proportionality, right intention, and probability of success. The eighth consideration is reserved for an inevitable engagement and involves right conduct in wartime. In his 2020 encyclical Fratelli tutti, Pope Francis urged us to consider that “it is very difficult nowadays to invoke the rational criteria elaborated in earlier centuries to speak of the possibility of a ‘just war.’ Never again war!” Clearly, it's never enough simply to declare a cause righteous in one's own mind and issue a call to arms.

References

Isaiah 9:5-6; 11:1-9; 57:19; Jeremiah 6:14; 8:11; Matthew 5:9, 21-26, 38-48; Luke 6:27-36

The Challenge of Peace: God's Promise and Our Response by USCCB, 1983

What Does the Church Teach About Just War? by Paul Wadell (Liguori, 2005)

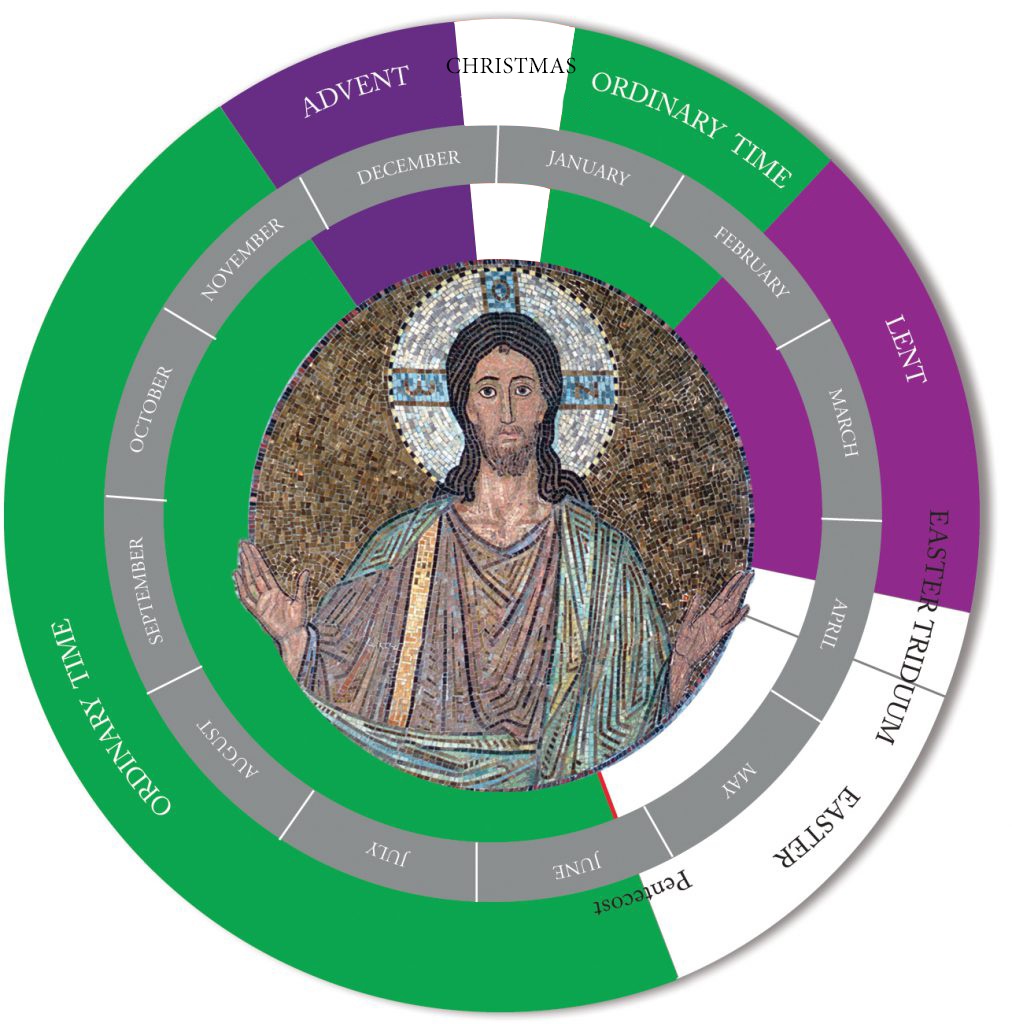

To be exact, three days on the liturgical calendar honor buildings—and another celebrates a chair. Since most Catholics think of feast days as memorials of saints and martyrs, the notion of venerating places and furniture can sound more than a little odd.

To be exact, three days on the liturgical calendar honor buildings—and another celebrates a chair. Since most Catholics think of feast days as memorials of saints and martyrs, the notion of venerating places and furniture can sound more than a little odd.