“We three kings of Orient are/ bearing gifts we traverse afar.” Nowhere in Matthew does it claim there are three. And Matthew never calls them kings. They are magi, hereditary priests of the ancient Medes and Persians. From this talented crew we get the word magic. But you can’t make a decent song out of “we unnumbered magi.” At least the carol gets one thing right: This group of wise fellows does bear gifts.

So how did kings get into the picture? Lay this at Isaiah’s door. He prophesies that kings will walk by the light of the Lord to Jerusalem. Their caravans will indeed bring gifts of gold and frankincense—but alas, no myrrh in Isaiah's vision of this scene. Gold symbolizes wealth and power. Frankincense, used in prayer, represents the divine Presence. Myrrh prepares bodies for burial. It's an ominous sign that would make a startling gift.

Matthew’s gift-bearers are wise men for sure. There is something "magical" about their foresight. Power, divinity, and death are three sober elements that will accompany Jesus from Bethlehem to Jerusalem. These were strange birthday presents to be sure. But they were appropriate honors for the King of the Universe, the Divine Son, and the crucified Lord.

Gold. Frankincense. Myrrh. These were the gifts Jesus received long, long ago. But we also bear him gifts at every Eucharist: Bread. Wine. Our financial sacrifice. These are all "made by human hands" one way and another. And, as Jesuit Roc O'Connor suggests, these are gifts transformed and returned to us as Body and Blood of Christ, and redistributed resources for those in need.

More gifts come to us by way of this shared Table. Grace pours out on the assembly. But grace can seem like one of those white elephant gifts: Now that we have it, what do we do with it? Church teaching describes grace as internal sanctification. We're made holy, fit “temples of the Holy Spirit,” as Paul assures us. This isn’t about spiritually fumigating your chest cavity. It’s about becoming, like Mary, God-bearers: those who carry the divine presence wherever we go.

Grace moves at God’s initiative. We can’t muster it up by sheer force of moral living. Paul says we can try to save ourselves by obedience—but we will surely fail. Grace forgives sin, and rescues us from every evil. This is one gift you don’t want to put at the bottom of a closet.

Scripture

Isaiah 60:1-6; Psalm 72; Ephesians 3:2-6; Matthew 2:1-12; 1 Corinthians 6:19

Books

At the Supper of the Lamb: A Pastoral and Theological Commentary on the Mass - Paul Turner (Archdiocese of Chicago: Liturgy Training Publication, 2011)

In the Midst of Our Storms: Opening Ourselves to Christ in the Liturgy - Roc O'Connor, SJ (Archdiocese of Chicago: Liturgy Training Publication, 2015)

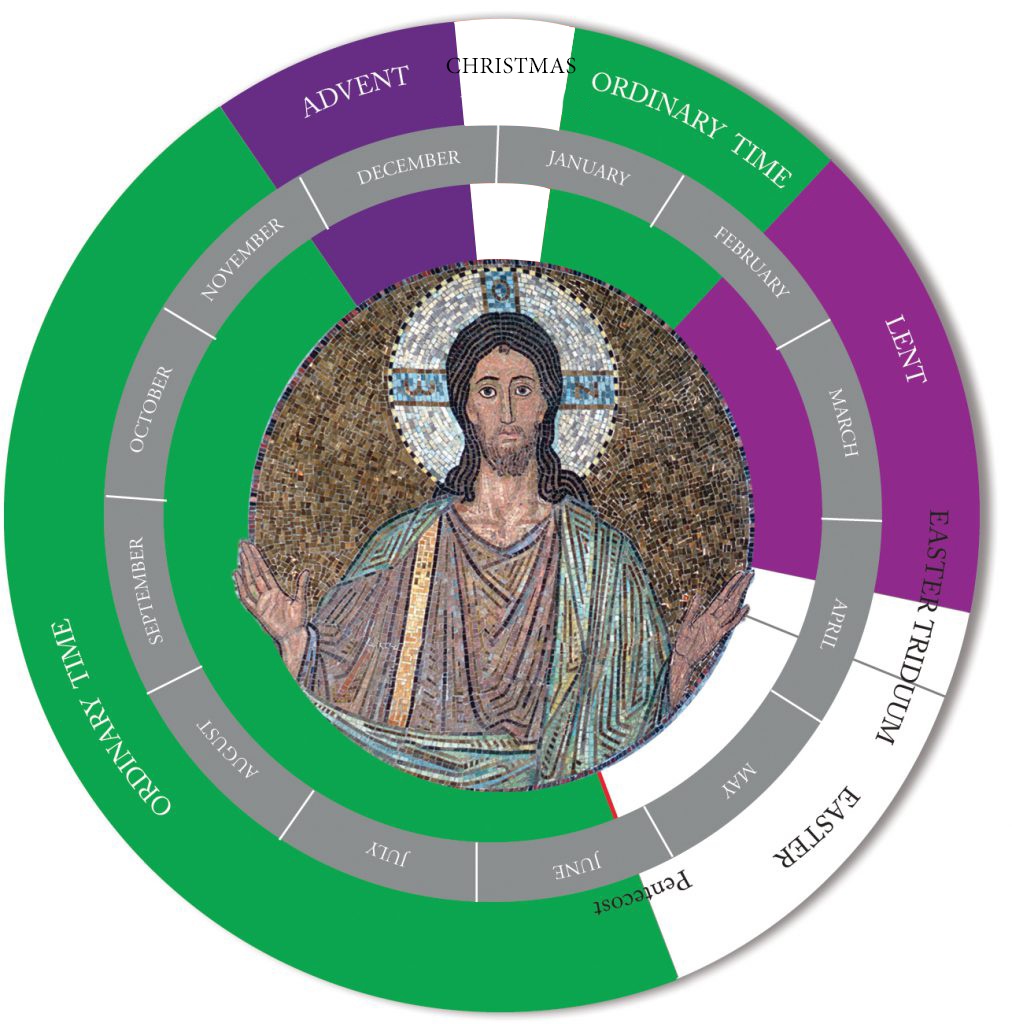

To be exact, three days on the liturgical calendar honor buildings—and another celebrates a chair. Since most Catholics think of feast days as memorials of saints and martyrs, the notion of venerating places and furniture can sound more than a little odd.

To be exact, three days on the liturgical calendar honor buildings—and another celebrates a chair. Since most Catholics think of feast days as memorials of saints and martyrs, the notion of venerating places and furniture can sound more than a little odd.